The arguments against the transfer of idle funds of PhilHealth to finance some unprogrammed appropriations are becoming more predictable, repetitive and unconvincing. I summarize below those major arguments.

No. 1, if those unprogrammed appropriations are indeed important, they should have been included in the regular programmed appropriations so they can get regular and not standby funding.

No. 2, much of the congressional “pork” budget was inserted in programmed appropriations, bumping off certain unprogrammed fund projects so that unprogrammed allocations increased to P731 billion from P282 billion in 2024.

No. 3, PhilHealth is a social health insurance fund and not a bank, and people’s premiums cannot be tapped for other government spending, and PhilHealth should not call the unused fund “savings.”

No. 4, high out-of-pocket expenditures (OOPE) in the Philippines, 46% of which are health expenditures, are the third highest in Southeast Asia and only lower than Cambodia and Myanmar.

Since those arguments are repetitive and bordering on being emotional, they are easy to rebut. In this column last month, “On unprogrammed appropriations and Secretary Ralph Recto” (July 30), I already provided some answers to the above claims. I wrote the following:

On No. 1, “The programmed appropriations, our expenditures, are so many that current and future revenues will not be able to catch up resulting in a huge budget deficit… huge interest payments that add more pressure on expenditures, in the first half of 2024 our interest payment was already P377 billion, likely to reach P750 billion in the full year 2024… The budget deficit for 2024 and 2025 would be at the 2023 level of P1.5 trillion.”

On No. 2, “out of the P731 billion in unprogrammed appropriations for 2024, the potential congressional pork barrel fund would be P225 billion on “strengthening assistance for government infrastructure and social programs.” The rest, or P506 billion, is earmarked for foreign-assisted projects (FAP), the Philippines’ counterpart funds, social programs for health and education, etc.”

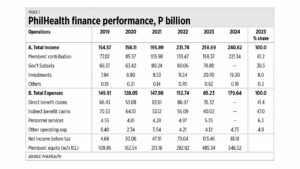

On No. 3, people’s premium payment will not be used. Members’ contributions from 2021 to 2023 ranged from P106 billion to P158 billion. And the members get benefit claims from P85 billion to P153 billion over the same period. It is not members’ money that will be tapped by the Department of Finance (DoF) for unprogrammed appropriations, but money from gamblers and bettors (PAGCOR and PCSO), money from drinkers and smokers of legal products (alcohol and tobacco tax revenues), the average P80 billion/year over the same period (see Table 1).

On No. 4, out-of-pocket expenditures per capita in the Philippines of $91 per person in 2021 was actually higher than those in Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Indonesia, India and Thailand. Valued in purchasing power parity (PPP) also in 2021, the OOPE per capita in the Philippines of $219 is again higher than those six countries.

I think those numbers on OOPE per capita refer only to National Government health spending (DoH, PhilHealth, UP-PGH, hospitals for AFP, PNP, Veterans, etc.). It’s possible that health spending by local government units is not included yet in the World Bank data. I refer to big hospitals owned and funded by cities and big municipalities.

Consider also this fact: Manila City has the greatest number of public hospitals per square kilometer of land. There are four big DoH hospitals (Jose Fabella, Jose R. Reyes, San Lazaro, Tondo Medical), the lone UP-Philippine General Hospital (PGH) and five or six city-owned hospitals.

Following the hypothesis or narrative that “more public health spending equals better health outcome,” can we argue and state with strong confidence that Manila City residents have the best health outcome, possibly the healthiest people in the Philippines? I doubt it.

The DoF is correct in tapping those idle funds of PhilHealth, especially money from gamblers, drinkers and smokers, to fund some unprogrammed fund projects. It is correct in avoiding to borrow another P90 billion, which when contracted at 6.4% interest rate (average for 10-year government bonds) would mean P5.76 billion in yearly interest payments alone, plus yearly principal amortization.

The detractors have spoken repeatedly, and they have presented no new arguments that will help the country reduce the deficit, reduce borrowings or reduce interest payments.

Onwards, the DoF should not stop tapping the idle funds of government corporations to reduce the deficit. In the long term, it should privatize some or many government assets, lands and corporations. Big-ticket items like NAIA land itself of 636 hectares and New Bilibid Prison land of 447 hectares since the DoJ is building big regional jails and abandoning the national penitentiary.

Privatization revenues should be used entirely to reduce the public debt stock, not earmarked for any department or public programs and projects.

Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. is the president of Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. Research Consultancy Services, and Minimal Government Thinkers. He is an international fellow of the Tholos Foundation.