There are three phrases that I regularly read used in the continuing opposition by health activists and lobbyists over the excess PhilHealth (Philippine Health Insurance Corp.) funds.

One is “defunding PhilHealth.” “Defunding” means that a budget is slashed from xx billions to zero. This is not happening so the term is plain emotional and dishonest.

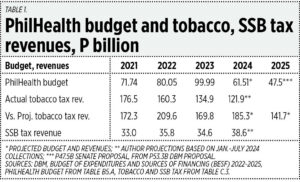

In 2023, PhilHealth had a budget of P100 billion, largely sourced from tobacco excise tax collections, which peaked at P176 billion in 2021. Under RA 11346 of 2018 which raised sin tax rates, 50% of excise tax revenues from tobacco, alcohol, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) should go to PhilHealth and the Department of Health (DoH).

When the tobacco tax rate increased from P50/pack in 2021 to P55/pack in 2022, tobacco smuggling and illicit trade exacerbated and tobacco tax revenues declined for the first time, down to P160 billion in 2022. The PhilHealth budget declined to P61 billion in 2024.

Then in 2023, the tobacco tax rate further increased to P60/pack and tobacco smuggling got even worse and government tobacco tax revenues further declined to only P135 billion, or P41 billion less than 2021’s level. In 2024, the tax rate further increased to P63/pack, the illicit tobacco trade worsened again, and the projected tobacco tax revenues will further decline to only about P122 billion.

The health lobbyists demanded an even higher PhilHealth budget for 2025 of up to P172 billion, even if they knew that their beloved tobacco tax money keeps declining. They did not get what they wished so now they blame the departments of Budget and Finance. This instead of blaming the high incidence of illicit trade in tobacco and the shift of smokers from legal to illegal tobacco, plus the shift to vapes from tobacco.

Anyway, PhilHealth will still get funding despite the declining tobacco tax money. PhilHealth will not be “defunded” in 2025 but it will receive fewer funds — P47.5 billion based on the Senate budget bill for 2025 (see Table 1).

The second phrase I see is “PhilHealth indirect contributors.” The indirect contribution to PhilHealth is the 50% share from excise tax revenues from tobacco and sugar-sweetened beverages. So, are the health lobbyists implying that the non-direct contributors to PhilHealth are the smokers, vapers, and sweet beverage drinkers? It does not sound logical because most patients are prohibited by their attending doctors from smoking and eating sweets.

The third phrase I read is “Insurance contract liabilities (ICL)… amounted to P1.128 billion.” As discussed last month in this column, “On the PEB in London, the PhilHealth funds, and the US elections” (Nov. 5), I ex-plained that “ICL is Present Value of Future Outflows minus Present Value of Future Inflows… So ICL are just estimates, not backed up by actual claims or contracts with hospitals and health professionals.”

Since ICL are just estimates based on certain assumptions, when the assumptions change, the ICL also changes significantly. See the fluctuation and variability of ICL estimates: P1 trillion in 2020, P0.34 trillion in 2021, P0.27 trillion in 2022, P1.15 trillion in 2023. Even that P1 trillion ICL is just hypothetical and not actual claims made by healthcare providers like hospitals.

One mistake that was made by the health lobbyists and activists was when they moved for the earmarking of tobacco tax revenues for PhilHealth and the DoH. They are happy when there are more smokers and drinkers of legal products because then the tax revenues increase. When smokers shifted to illegal or illicit products because of the high tobacco tax rate, the revenues declined, and funding for PhilHealth declined.

CREDIT RATINGSLast week, on Nov. 26, S&P raised the Philippines’ credit rating from “BBB+ stable” (given in April 2019) to “BBB+ positive.” So, the next ratings upgrade for the Philippines would be “A-,” and will hopefully be given within the next 12 to 24 months. This is good news for us.

I noticed that several developed countries have very high ratings of AA to AAA yet have had a high level of corporate bankruptcies recently, like Australia and Germany. In contrast, a number of East Asian economies also have high credit ratings but are seeing flat or a declining number of bankruptcies, like Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and South Korea (see Table 2).

The challenge for us, especially the government economic team, is to attract those failing and migrating companies to move from North America, Australia, and Europe to the Philippines. We have third fastest GDP growth in Asia next to India and Vietnam, have improving credit ratings, declining inflation and unemployment rates, and other positive factors.

Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. is the president of Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. Research Consultancy Services, and Minimal Government Thinkers. He is an international fellow of the Tholos Foundation.